With much focus on the developments in the increasingly strategic geo-political Indo-Pacific region, current analysis in the West has shifted to the potential for military intervention by China in Taiwan. By contrast, domestic discussion within China is increasingly shifting to whether there needs to be regime change to secure China’s place within the wider global order.

As an analyst with a keen interest in the region, I am often asked whether I think there will be some form of military intervention in Taiwan and when. People are surprised when I suggest that the current hostilities mask the economic drivers – the real issue in play.

Looking through the largely white noise around the realpolitik of the soft power – hard power rhetoric and rising nationalism, I believe that China is fast approaching an inflection point with the next six months being critical in determining China’s future as a global citizen or its return to the closed society as lived under Mao.

This article will look at the economic imperatives behind the debate and argues that the changed economic narrative points more to China requiring a regime change rather than resorting to military conflict over Taiwan. Military conflict, whilst playing to the domestic / wolf warrior audience, does not address the changed stature of China in the global politico-economic order. Before anyone accuses me of encouraging insurrection in China, when I talk of regime change, I refer to a change that is needed in current political dogma that currently has the Communist Party of China (CPC) as God to all Chinese citizenry. This dogma is a retreat by Xi Jinping to traditional Maoist thought in which the Party is the central controller.

Might is right

The question is whether Xi Jinping has the will power to change the narrative he has imposed on the country following the introduction of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) or whether there is a need for new leadership. This is not an attempt to diminish some of the many achievements under Xi Jinping’s reign, such as elevating a huge portion of the Chinese population out of poverty, but this asks the question as to whether the political approach used to achieve these goals is appropriate for China’s next phase of development and whether it is sustainable.

The economic reality that China and the CPC is currently facing suggests that it is not prepared to change its policy direction. It does so as it fails to recognise that China, through the successes under the BRI, are more integrated into global trade. The consequence of this success is that China needs global markets more than ever before and simply cannot continue to weaponize its growing economic clout.

There appears to be a growing domestic awareness of China’s dependency on global markets as economic growth has been constrained by resource and energy security. It does not have all the resources needed to sustain its continued economic growth. Take for example its reliance on iron ore and the price that it is now paying for this resource as it wants to maintain its infrastructure development targets.

The CPC is typically obfuscating this reliance by playing to the wolf warrior narrative by strategically weaponizing trade sanctions and targeting trade bans that will have little impact on its domestic and global ambitions. For example, China relies heavily on the following commodities as shown by their global import activity: 73% of crude oil, 90% of iron ore, 55% of bauxite, 86 % of LNG.

On the other hand, as far as securing its energy requirements, China is largely independent with regards steam coal (it imports a mere 2.38% of its needs) and coking coal (importing only 13% of its domestic consumption). It therefore makes strategic sense for China to pursue coal power stations as it can readily provide source materials. It can comfortably target Australian coal and create a climate change distraction from its true intent by making Australia the enemy of climate change “science”.

This is an economic strategy portrayed as being a geo-political issue. Australia should be used by other like-minded countries as a case study to learn how China obfuscates its economic agenda by using geo-political distraction. On the one hand, China does little to interfere with iron ore imports as this resource is key to its development yet will “diplomatically ban” coal imports from Australia. China, with the help of the UN and other “green” institutional bodies, is using its internal energy strength, coal, to effectively de-industrialise Australia through the creation of energy scarcity within Australia. It is ironic that China only takes 17 to 18 days to produce the total annual emissions of Australia, yet they have successfully managed to isolate Australia for special treatment.

China appears to be using game theory in its approach, particularly as it sees the Western trade alliance as not wanting to engage in retaliatory measures that would bring about a global tariff war. In their minds, it is a gamble worth taking. After all, the West is hampered by civil institutions and an unrelenting adherence to the rules-based order. This philosophical divide gives China the strategic advantage in economic terms and buys it time not just to play catch up but to direct and lead the narrative. When Xi Jinping in 2019 announced the “New Era” i.e., socialism with Chinese characteristics, it was based on the belief that the Soviet Union was destroyed by cultural subversion. Russia failed as it allowed economic liberalization to bring change by undermining the state’s political monopoly.

Chen Yixing, Secretary General of the Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission, also feeds the game theory narrative by advising Xi Jinping that the global mega trend is the “rise of the East and decline of the West”. This not only miscalculates China’s chance of winning military conflict, but also the rise of other Asian countries, such as India.

Politically, Xi Jinping has turned the country back to a Maoist approach, with a strong Leninist flavour to development, by placing the Party above the law. It is the Party’s goal to win the initiative and have the dominant global position. The result has seen a move from an authoritarian to that of totalitarian state within China. Post-Mao, there was a form of separation of the State from the economy, but now there are no longer any limits to the Party’s authority in any sphere of life.

While there has been a growing awareness of China’s assertiveness under Xi Jinping’s nationalistic call to restore China’s pride after “a hundred years of humiliation”, many fail to appreciate China’s increasing reliance on external economic markets. The CPC under Xi Jinping’s leadership ignores the symbiotic relationship that has emerged with open global markets. Ignoring this symbiotic relationship is a tactical weakness in their game theory approach to Taiwan and other countries.

What are the economic drivers that make the “safe bet” choice a weakness?

China’s growth and rising middle class has created a dependence on the outside world, creating a greater strategic vulnerability. In simple terms, China’s domestic market can sustain a level of GDP growth, but foreign resource dependency is now greater than ever.

The low unemployment rate is given as an indicator of the success of socialism with Chinese characteristics, but it masks a structural employment issue that will increasingly take China into the middle-income trap. In the 16-to-24-year age group, unemployment stands at 13.8%, highlighting a mismatch between jobs and skills as the service sector recovers very slowly. Exacerbating this structural economic problem is the decline in the number of manufacturing workers as the service industry worker supply goes up. This imbalance has brought about a wider geographic spread of discontent as factories cannot readily open due to a lack of available labour in Western China and an oversupply of service industry workers in Eastern China.

In the past, domestic tensions were eased as these service sector workers found employment in other countries, such as Taiwan, particularly with regards technology-based jobs. Covid-19 has slowed this service-based labour export considerably and magnifies the weakness in China’s claims of self-sufficiency. This vulnerability is growing as more countries ban highly skilled service workers from being employed in positions that are seen to undermine national security. Initially this ban was confined to the cyber world but is now extending to educational and research institutes around the globe.

The CPC understands this as it uses its propaganda machine to extol the virtues and success of China during its 100-year celebrations. It is no co-incidence that the budget for “stability maintenance” within China is over the USD 200 billion mark, highlighted by the recent deletion of 7 million online critics of the CPC by the Cyber Administration of China, on the grounds that these online posts “distorted” China’s real history. Whether the CPC likes it or not, Chinese citizens are increasingly aware that they need other countries for employment.

There has also been a failure to recognise that, whilst “wolf warrior” diplomacy may resonate in the domestic arena, it has failed globally by undermining all of China’s soft diplomacy efforts. This is particularly evident in the failure of the EU parliament to ratify the recent EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI). Underpinning this ratification failure is the progress of the EU in introducing the economic equivalent to NATO’s Article 5, i.e. an attack on one economy is an attack on all democratic economies. Some would argue that this is the first step in a global tariff war.

With the trend with global consumers taking the opportunity to support targeted farmers, fishers and vintners as China loses the “soft diplomacy war”, this coalition of thought is a significant risk to China’s reliance on ambiguity to play out its “gamble” to dominate markets by exploiting the lack of unity in approach by global markets.

There is a realisation that the EU as a market and in terms of per capita GDP is the largest in the world. Although made up of 27 member states, with some close supporters of China, the US-EU dialogue in October 2020 around China highlighted the EU’s leverage in the economic realm. This new awareness has seen EU-based companies not so much looking to fully decouple from China, but to rebalance their trade arrangements by reducing reliance on China-based supply chains.

Realising the growth of the cyber world, the EU parliament introduced a global connectivity strategy in January 2021 that aims to strengthen the EU’s role as a geo-economic actor with a single narrative. Included in this is the EU committing to phasing out 5G technology built by third countries that do not share European values and standards. If fully implemented, it will severely curtail China’s Digital Silk Road trade ambitions with the concomitant knock-on effects on employment and access to technology advances. This will also have a negative impact on their ambitions to have the Digital Yuan replace the USD in foreign currency transactions as part of the BRI and Digital Silk Road extension into Europe.

With the changing EU and Indo-Pacific economic context, will Taiwan be the flashpoint that will validate the Thucydides trap?

China has upped the ante with regards Taiwan such that it may well become the military flashpoint. China’s sovereign claims in and around the waters of Taiwan and extending to first island chain claims in the South China Sea are increasingly being questioned by international bodies. Unfortunately, this has expanded their military ambition more due to an anxiety to protect vital supply lines, increasing the risk of outright military confrontation.

But there is another side to this confrontation coin. Taiwan also reveals the true economic nature of China’s sovereignty claims. Their pursuit of Taiwan and the South China Sea gives greater context to the narrative that real power is vested in the economy and access to vital resources. And this is not unique to Taiwan.

For example, Xinjiang occupied a strategic role for Beijing due to it bordering three of five central Asian states. With its 22 ethnic groups, Xinjiang was and is still not a homogenous culture and shares very little in the way of cultural connectivity to the Mainland. It was forcibly incorporated into China during the Qing era in the 17th century and was seen as a buffer with Russia and to protect China’s trade across Asia and Europe. Formally integrated into China in the 18th century, it was only in 1949 that the region was legally brought under the control of China. Xinjiang has always been important for China’s economic success, with its modern-day importance being a secure and reliable supply of crude oil and gas as well as cheap manufacturing labour. Whilst Xinjiang is an imperial legacy that provides China with greater economic security, this comes at a considerable security and political costs.

In many aspects, Taiwan shares similarities with Xinjiang, particularly with regards historical claims that they are a sovereign part of the Mainland. However, Taiwan is better placed to pursue its own economic / political agenda as it has never been formally incorporated into China. Therefore, it is being increasingly treated as independent from Mainland China, hence the escalation of the geo-political and military rhetoric by Xi Jinping. Claims that China will “bash the heads until they bleed” of those that support Taiwan’s independence plays to the wolf warrior narrative of China’s historical victim status. It is also based on the gamble that the West and its allies will not step in to defend Taiwan in the event of a military intervention by China.

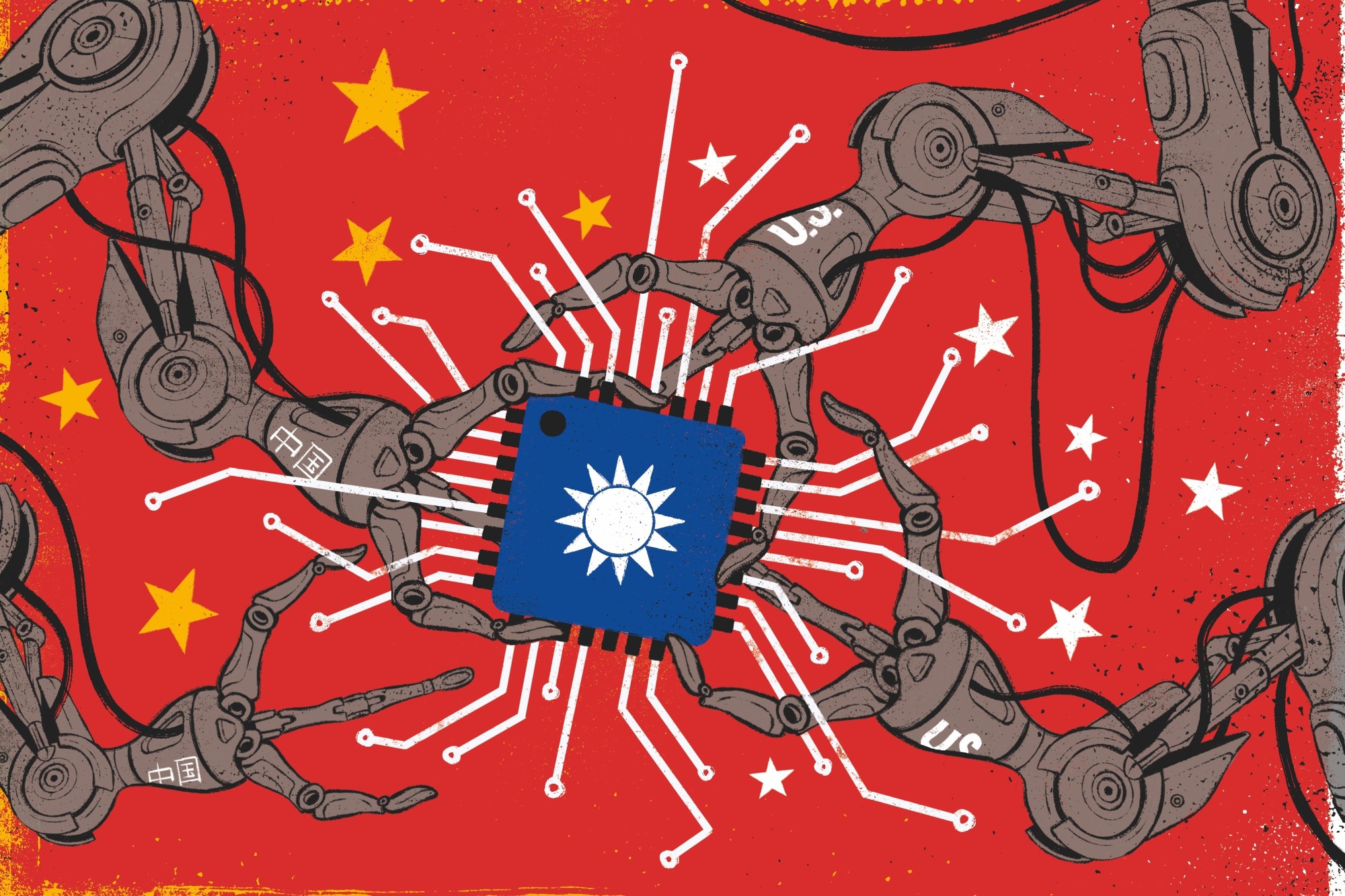

More importantly, this rhetoric deflects from China’s real economic intent. Besides control of important sea trade routes through the Taiwan Straits and the South China Sea, China has built a strong reliance on Taiwan’s semiconductor manufacturing and technology capability. This is a fundamental weakness for their ambitions of creating a single trading software platform under the Digital Silk Road as well as its ambition to become the global economic leader in the cyber world.

Whilst China does lead in certain sectors of the digital arms race, it is still a follower in many regards. Ranked 16th out of the 63 leading digital / technology countries, it is seriously lagging in the digital technology space, ranking only 27th. This weakness has the potential to derail China’s growth ambitions, particularly its desire to be the dominant digital economy.

A closer look at the semi-conductor development chain shows that this industry is central to the development of 5G, Cloud-based and Internet-of-Things (IOT) economic growth activities. However, two of the three supply chain phases account for 94% of the value along the chain, with the dominant manufacturing phase (55% of the supply chain) essentially being controlled by Taiwan. The design phase, that accounts for 39% of the supply chain, is essentially controlled by the US and South Korea. This weakness was further exposed by the recent liquidation application of the mainland microchip manufacturer Tsinghua UniGroup. Essentially, Taiwan is more of an economic imperative for China than a matter of geography.

Proof of this has been China’s recent “pineapple war” with Taiwan. Ninety percent of Taiwan’s pineapples are exported to China, so picking on an export product that can do harm to the adversary without depriving itself from a strategic input showcases the use of economic bullying as a weapon. These attempts to economically disrupt Taiwan have had the unintended consequences of encouraging other countries to support Taiwan through increased import / export activity as well as to enter into free trade agreement negotiations.

The international community’s growing support for Taiwan is mainly due to its growing importance in global supply chains, with microchips as the new oil and the semiconductor industry as Taiwan’s “silicon shield”. Taiwan remains vital for the likes of Google, Apple, Amazon as well as for Chinese tech behemoths such as Huawei and Baidu. If these Chinese firms want to gain dominant brand status, they will need Taiwan.

China’s push to create more “active” microchips that are less reliant on improved technology will make Taiwan less economically attractive. Likely, a military intervention to retake by force the “renegade province” will also become less attractive.

Picture credits: Adria Fruitos / Los Angeles Times

Be First to Comment