It is not that Europe and the US were unaware of China’s development throughout the 20th century. Waking up in 2020 to China running neck and neck with the US and eying Europe as its main export destination could be, to some extent, attributed to the underestimating the potential of such a unique demography and distinctive national motivation rooted in collective memory dating centuries ago.

One should not exclude a set of international circumstances spanning from politics (cold war), science development (introduction of semiconductors), technology progress (3rd and 4th industrial revolution), trade expansion (globalization of supply chains) and last but not least global health (the Covid-19 pandemic).

Although there is a wide array of mutually intertwined parameters that will shape the upcoming years and the relationship between China and Europe on the economic and political field, some crucial things that will most significantly contribute to the outcomes can be outlined. The three key issues discussed in this report are China’s 14th five-year plan, the adoption of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the European Union’s Foreign Direct Investment screening mechanism.

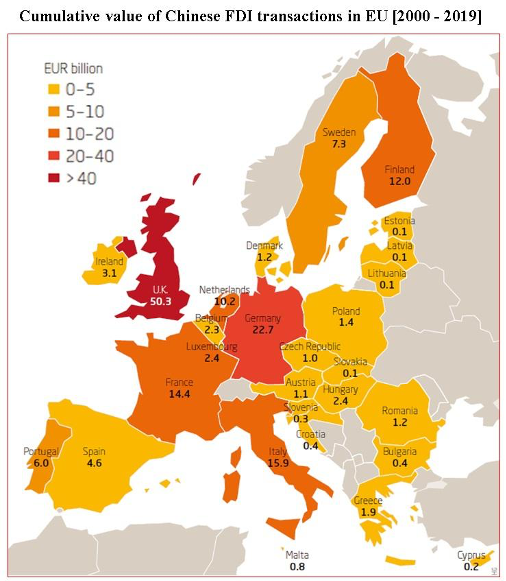

Though pictures tend to speak louder than words, numbers are key to drawing proper conclusion, and the thing with numbers is that they hardly lie. This is why exacerbated threats of China conquering Europe, along with constant taunting of its debt traps looming over Europe, can easily be refuted and debunked by a relatively quick analytical assessment.

The story behind a huge number of dots and red flags on world maps showing Chinese investments, that later get cancelled, shows how fragile, inconsistent, superficial and unreliable planning has been conducted from the side of the investor – compared to the understanding and past business practice of European market. Specifically, Chinese companies, mainly state-owned enterprises (SOEs), sign dozens of Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs) with other parties – mainly public enterprises (cases of coal fired thermal power plants in Southeastern Europe where national power companies are the other contracting party), or the state itself (cases of highways in Southeastern Europe).

The key problem is that Chinese SOEs have been signing so many MOUs in the past years that they have essentially devalued the notion and purpose of an MOU as it is viewed from the EU/US perspective (both academic and business one). MOUs do have a preliminary estimated budget, but the Chinese ones are typically accompanied by a “legally not binding” provision. This results in the problem of reliability of the project if one would tend to see an MOU as a confirmation that a project has commenced, and thus put in on certain map of projects.

Figure 1 – Cummulative value of Chinese FDI, 2000-2019 (Source: Rhodium Group / MERICS)

As illustrated in Figure 1, the cummulative value of China’s FDI in the EU for the 2000-2019 period shows a very encouraging feature Europe should be well aware of: most of the Chinese direct capital investments went to Western Europe and in those markets with stable democracies, rule of law and appreciation of European values, giving a Eurasian meaning to the saying “money talks”.

It is not the quantity and scale-up game that China can lose, it is the quality and performance one. Which is why performance issues and quality assessment was not an issue when developing capital infrastructure investments in Latin America, Africa and Indonesia, but turned out to be a major hurdle when trying to do the same in Europe. Building highways in Africa is different from building highways in Europe, as was seen in Poland with the case of COVEC consortium withdrawal in 2009/2011, or with the ongoing construction of a 129 km highway for 1.69 billion euros in Montenegro. The difference is that in European countries, both in the EU and EU candidate countries, the investment and overall society feature a stricter regulatory framework and public scrutiny for underperforming.

It is safe to expect that China will remain primarily self-centered with respect to its state-owned enterprises (SOEs), who are trailblazers of the capital infrastructure investments endeavors in Europe, regardless whether they are seen as a part of the Belt and Road Initiative or because of the 17+1 platform. Those thinking that China will be restraining its SOEs in their overseas investment quests should rethink their stand. Its leading credit rating agencies maintained AAA scores for its leading SOEs despite their underperforming and a wave of defaults accumulating to an almost 4 trillion EUR debt.

As for 2021, the first important checkpoint in 2021 will be the first week of November and the venue will be Glasgow, Scotland. There, the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) will take place, as it was delayed in 2020 due to Covid-19, as the 5th (will turn out to be 6th) anniversary of the Paris Climate Accord. Going back to the smallest common denominator of China and the EU – this being curbing the greenhouse gases by a certain date in the upcoming decades – it will be important to see what course will be taken by key stakeholders – the EU, China and the US. Once the goal (the “what”) has been identified and agreed upon, the means (the “how”) can vary as they are affected by a number of parameters.

However, as long as the means do not jeopardize the goal, the main concerns will be business competition, competition in research and development and investing in science. Less politics and more concrete results.

Download the full report here:

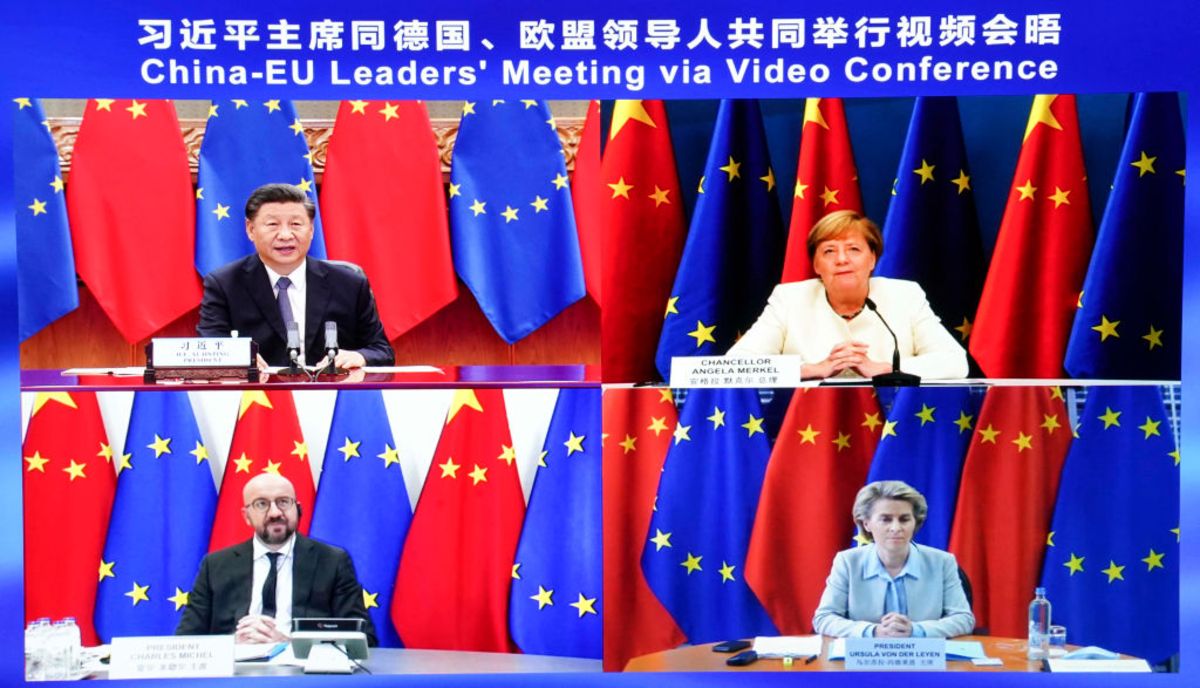

Picture credits: Pang Xinlei / Xinhua via Bloomberg

Be First to Comment