Recent developments between China and the world bring to mind a 1960s Buffalo Springfield song: “There’s something happening here—What it is ain’t exactly clear.” Realising a century-old dream going back to President Sun Yat-sen, China finally challenges the global economic primacy of the United States. However, both its domestic and international economic models raise serious sustainability issues. Never mind: China specialises in fixing big issues fast. But that could be in jeopardy if Beijing disregards, challenges or corrupts causes and values dear to the international community’s key influencers. If China is the new America, the USA will certainly put up a fight before passing the keys to the world. Meanwhile, China-based businesses often find themselves in the crossfires of trade wars, internal and international political showdowns.

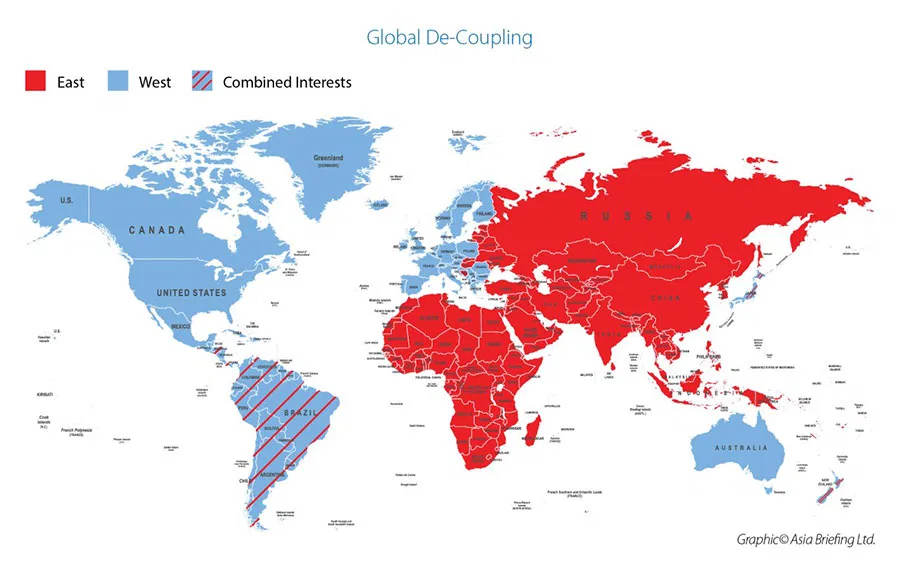

China has seen itself as the land of dialectic contradictions from Lao Zi to Mao Zedong and Xi Jinping. Business reality confirms that notion: it has been the most dynamic emerging market for decades, but since 2014, more than half of the multinational managers polled annually by the EU Chamber-Roland Berger joint China Business Confidence Survey reckoned that “the ‘golden age’ in China is over for multinational companies”. Meanwhile, its market remains reliable and profitable: in the same study, half of the surveyed multinationals saw it as a top-three strategic priority. But polarised and politicised debates continue — in author Luke Patey’s words a “dichotomy of overreaction and naiveté”. Fans hail a Chinese Dream of peace, harmony and a shared vision for humankind—in Beijing’s humble words. Alarmists see the global emergence of Chinese goods, services and ideas as a conspiracy toward Communist world domination. Both sides justify vitriolic or violent language by demonising the other. The debate has direct policy and business implications, inspiring a recent world map of ‘decoupling’ with neatly divided Eastern, Western and combined economic realms.

Source: Asia Briefing Ltd

When did the trend begin?

Popular lore often blames the current Covid-19 pandemic or the preceding trade wars between China and initially the United States, later Canada, Australia, Japan, South Korea, the EU and gradually most of Beijing’s top trading partners. These crises enhanced existing challenges but to add another musical pun, they didn’t start the fire. Certain trends were evident by the time the EU Chamber announced the end of the golden age for multinationals in China. Back then, the paper was quoted by a few global publications, but it was understandably ignored by the mainstream of executives and commentators. The world was under the spell of China’s decades-long double-digit GDP growth, rising living standards and Beijing’s mounting confidence in the wider world. Meanwhile, others already noticed China’s declining curves in both tangible and less tangible indicators of global integration: the share of foreign investment in GDP, outward investment and rankings such as the McKinsey Global Exposure Index.

Ironically, both trends have continued into the present: China demonstrably cools towards global economic integration while enthusiasm for its ‘reform and opening’ is unabated among its population and supporters. Testimony to the foresight of the 2014 EU Chamber paper’s authors was that within a year, Beijing announced Made in China 2025 — a government intervention programme to reallocate multinational market shares to domestic firms in key sectors such as semiconductors, new energy vehicles, IT, robotics, aviation, certain medical industries and more. The plan contradicted China’s World Trade Organisation (WTO) commitments, and the predictable international outcry made Beijing somewhat tone down the surrounding campaign. But the direction remained, both in China’s soaring rhetoric of victimhood on one side and responses from foreign diplomats, observers, investors, business and trade partners on the other. In 2019, Japan launched a sponsorship campaign for the repatriation of certain firms to the motherland. The same year, the European Union named China as a “strategic competitor” for the first time.

Up, on or out: three alternative China strategies

China’s government famously pushes through strategic agendas, come hell or high water. If Beijing is adamant on reviving the early People’s Republic’s Soviet-inspired vision of a mostly self-sustaining walled garden, international businesses might doubt its feasibility but must brace themselves for its possible realisation. However, contrary to the most pessimistic predictions, an increasingly inward-facing China does not mean the end of multinational involvement there. Market capitalism is the most agile non-natural force known to humankind, whose dynamics resemble the water that surrounds China’s former treaty ports, now rebranded as Special Economic Zones. Higher dams create more virulent forces on both sides. Inevitable valves and gaps, whether deliberate or accidental, create gushing channels of activity to compensate for the differing levels of information, resources, goods, services, human interaction and motivation. Firms still committed to China’s markets see three promising routes: up the value chain, on towards the country’s west or out towards global supply chains.

Up: scaling China’s value chain

Made in China 2025 and Covid-19 only hastened the erosion of China strategies by systemic forces: rising labour costs, digitalisation, automation and robotics, strengthening local competitors and more. Massive channels of commerce were voluntarily scaled down for environmental reasons, such as the recycling of American waste and the manufacturing of European solar panels in China. But while today’s China does not need foreign firms to manage cheap manual labour and repels polluting industries, foreign technology and know-how power its hopeful value-added industries. Ironically, Beijing needs imports for self-reliance. Increased domestic production of pork and rice require imported feeds, medicine and seedlings. Electronics champions like Huawei and Xiaomi rely on ASML chips and Leica lenses, while the state-owned internet monopolies that connect them subcontract high-end services to telecom firms like Nokia. The transmission of indigenous vehicles run on European, American, Korean and Japanese precision parts, as do China’s power stations, dams and forthcoming COMAC airliner.

It would be uncharacteristically simple if Beijing simply liberalised sectors where it needs foreign involvement. Studies find instead that such strategic sectors are among the most protected, perhaps in the hope of shortcuts to rapid innovation, perhaps to please domestic audiences. But it is equally possible that Chinese protectionism follows the same reverse psychology as the country’s tightening visa regulations: authorities raise hurdles hoping that only the most committed entrants can jump over them. If that is the case, the few multinational firms that have the offering, stamina and resources to scale the walls will find unlikely but lucrative opportunities on the other side. What were the chances of Tesla becoming China’s best-selling locally made electric passenger vehicle, or BioNTech and Fosun Pharma joining forces on Covid-19 vaccine technology, as it happened in both cases? Those multinationals followed the trusted career adage: make yourself indispensable.

On: for some, West is best

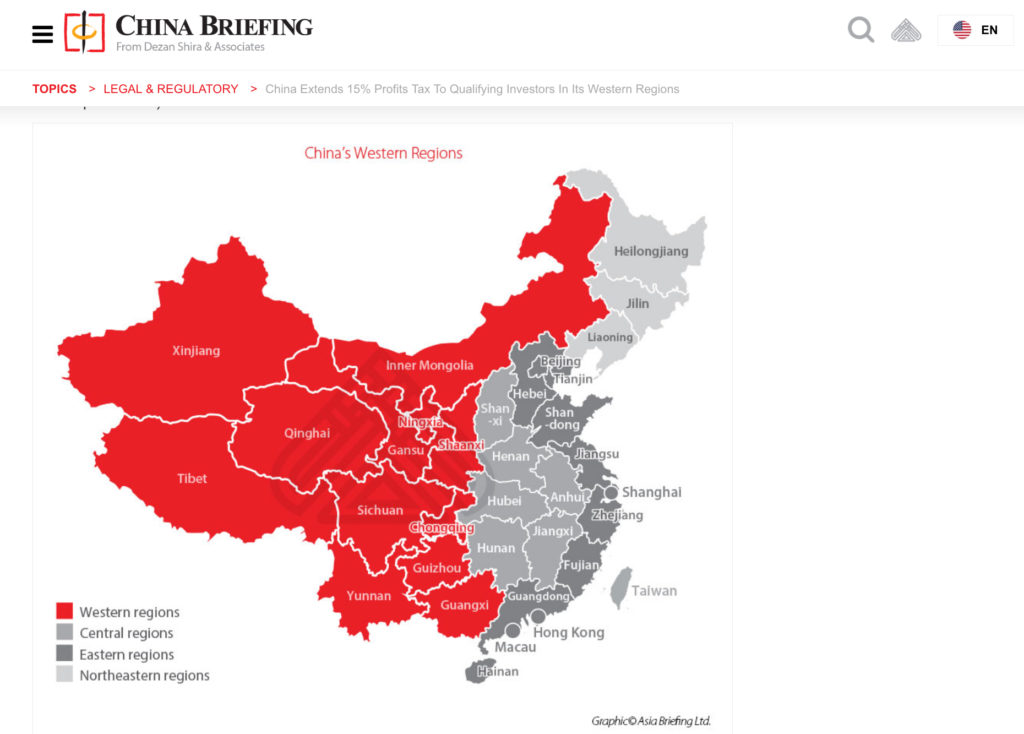

Scaling value chains is not an option for companies whose local success depends on squeezed manufacturing margins or imported novelty cultures. Many multinationals with the best track records in China are exposed to both: IKEA, Nike, Apple, Starbucks, food brands and perhaps even Tesla in the future. For such firms, exploring the country’s long-neglected interior can be a viable alternative. Beijing has offered incentives to firms going West since the start of the Millennium, including preferential land usage, tax breaks, government subsidies along a proliferating and improving network of SEZs with connecting infrastructure. One similarity between China’s Go West campaign and its nineteenth-century American namesake is the relative size of ‘the West’. A recent administrative map published by Dezan Shira Associates makes one wonder why foreign firms make so little and reluctant use of three-quarters of the country’s territory.

Source: Asia Briefing Ltd / Dezan Shira Associates

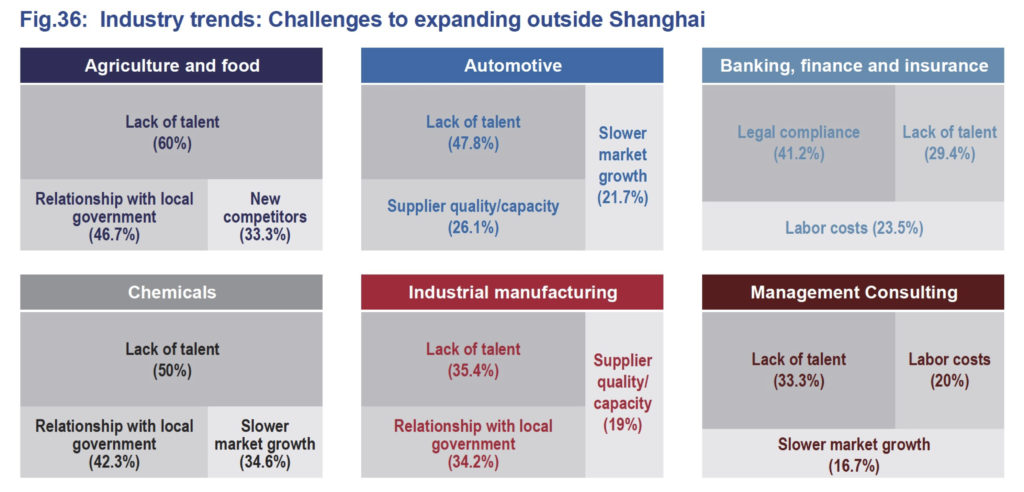

They have their reasons. A recent AmCham study found that half of the foreign firms going West faced talent shortages there. That is no surprise: for decades, Beijing encouraged the Eastward migration of talented workforce, both to meet ambitious urbanisation targets and to supply top-tier cities with low-cost migrant labour. The same study found that foreign executives found local government relations harder in the less developed West. But although the miles of red tape and sorghum-vodka saturated evenings may sound frightening, they pay off in nearly limitless opportunities, both organic and state generated. Though that is hard to imagine on a clotted Beijing highway, automotive executives know that car ownership rates in China are less than a fifth of the USA or EU, suggesting a promising market in the relatively undeveloped western provinces. Manufacturers and retailers of consumer goods like clothes, furniture and electronics may also find sweet spots of affordable labour and nearby clients there. Firms in mining, construction, infrastructure or healthcare may benefit from Beijing’s efforts to further develop the area.

Source: AmCham China

Out: in pursuit of global supply chains

If you wonder whether foreign investment is leaving China, follow the deniers and their inevitable ‘this-firm is quitting China and won’t be missed’ announcements. They seldom realise the irony, seeing market presence as a matter of loyalty rather than profitability. Indeed, some multinationals abandon China for ideological reasons: H&M, a European fast-fashion chain dualling Beijing over supply chains tainted by alleged human rights violations, is the highly visible tip of a looming iceberg. American, Japanese and South Korean firms in sensitive industries have suffered increasingly hostile politics for years, and repatriated manufacturing, sales or both to reduce risks. Intel, Sharp and Samsung divested that way, as did Taiwanese firms Quanta and Delta Electronics. Others exited due to slumping sales, including clothing brands Old Navy, Superdry, Steve Madden and Sony’s mobile phone brand. Politics and economics are hopelessly intertwined. Car makers Kia and Hyundai fled from Beijing’s politically orchestrated sales boycotts. Samsung phones, LG, Stanley Black & Decker and HP pulled out to avoid US trade-war tariffs. Microsoft, Google (Alphabet) and Apple all partially withdraw manufacturing, although their reasons and approaches to Beijing are different.

But business with China does not equal business in China, for both obvious and counterintuitive reasons. Many thriving firms never had direct presence in China or withdrew at one point. Contrary to predictions in 2007-8 when Beijing blocked them, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and other technology service providers weathered the disappearance of their PRC users rather well. Cosmetics firms like Body Shop have abstained due to mandatory animal testing. Firms like LEGO and Zara resisted manufacturing in China until it was necessary for expansion in the local market. That reveals the frequent overestimation of China’s pivotal role for developed economies. As a trading partner, China is on par with Canada for the United states and the Netherlands for Germany: significant but hardly unique. Moreover, much of the departing supply chain network will resume somewhere else. American tech firms can cooperate with the same Taiwanese and Korean suppliers in South-East Asia, and partnerships can even include Chinese firms abroad. Beijing’s restrictions have squeezed home-grown firms as much as foreign ones, and thanks to Belt and Road, the same Chinese supplier may be ready in Bangladesh or Indonesia. Befittingly, the beneficiaries of the transition may include the same overseas Chinese diaspora that sponsored China’s opening a quarter century ago.

Picture credits: Liu Jin / Getty Images

Be First to Comment