Predictably dramatic reactions followed Beijing’s late-March announcement of yet another modification of China’s Covid-19 case statistics. Some remained objective: Time Magazine remarked that “it was the eighth different definition of what constitutes a Covid-19 infection”. Others much less so: US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo called it an “intentional disinformation campaign that China has been and continues to be engaged in”. Comments on both mainstream and social media were as imminent and divided as expected, some defending China’s position and accusing the West of applying double standards, others plainly tarring Beijing with accusations of dishonesty and cover-up.

Both sides seem to have a case. Several states have made comparable revisions without triggering similar reactions. One must also account for what Robert McNamara called “the fog of war”, the lack of clarity during fast-moving cataclysms. But that did not seem to excuse China. Today’s global media thrives on bottom-up information flow and transparency. Twitter saturnalias where individuals probe, question and challenge institutional news sources now include Prime Ministers and Presidents. China is noticeably absent. On one side, its state-run media avoids unwanted topics, like the epidemic’s presence in its political leadership and armed forces. On the other, what happens on Chinese social media stays on Chinese social media. Its citizens are virtually absent from forums like Facebook and Twitter, and domestic alternatives like WeChat are virtually absent abroad.

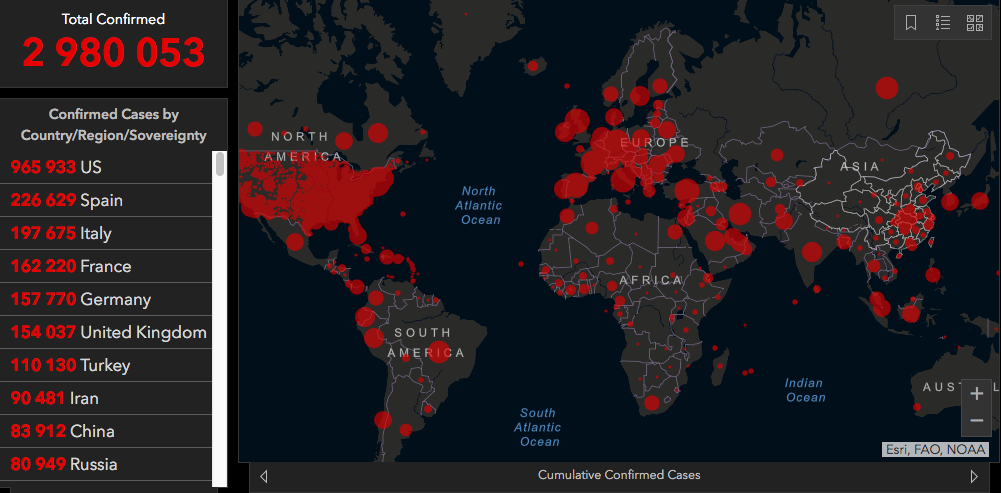

Uninhibited and judgemental, international public opinion responds to the absence of information from China the only way it knows how: emotionally. That is understandable: psychologists have proven that a consistent lack of stimulus causes discomfort and suspicion first, paranoia and panic later. It hardly improves matters that several governments, including China’s own, have presented the struggle with the pandemic through a combat rhetoric. Wars require human enemies, and nothing makes a nation an easier target than its own pomposity. Too often, international business leaders and decision-makers see China through the narrative presented to them: secretive, potentially deceptive and up in arms. The question is inevitable: is Covid-19 indicative of a larger issue with China’s self-published data? Can their numbers be trusted at all?

Through nearly two decades of China-based consulting work, the most frequent strategic error I have helped my clients address is forcing an external logic of causality onto China. Somewhat similarly to Cold War era American analysts who considered the Soviet Union, or even the Eastern Bloc, a single unit of decision-making, observers who witness China’s statistical revisions often assume unified cognition and action. They are aware of China’s unmatched state apparatus, its government surveillance system, its progress with e-commerce, mobile payment technology and an imminent social credit system to turn it all into an omnipotent central network. An uncommunicative Chinese state with so much data is bound to hide something, they conclude. When today’s numbers significantly differ from yesterday’s, isn’t one of those statistics bound to be a lie?

A closer look reveals a more nuanced picture. In the early 1950s, the People’s Republic modelled its statistical data collection and processing system after the Soviet Union. Unlike the essentially grassroot method in the West that started with England’s 1086 Doomsday Book and matured with the age of democratic elections, Leninist states start from the top with Five-Year Plans. Since its first Plan in 1953 until today, China periodically set overarching economic targets, then turned them into trickle-down objectives for entire sectors, then state-owned and later private economic units such as mines, firms, farms and universities. Resources were allocated according to that blueprint, and unit leaders were responsible to meet targets and report results. Eager for prospects, promotions and future resources, officials were motivated to deliver numbers by all means necessary, economic or administrative. Reported results became statistics, and in turn future plans.

But figures in such systems reflect affairs as they should be rather than as they are. Like the 1990s Eastern Europe where I started my consulting career researching the gaps between plan-based and actual statistics, China became painfully aware of the potential damage of such fictitious data-collection as it reconnected with global markets. The problem became so obvious that its economics-trained Premier openly questioned national GDP figures, inspiring the so-called Li Keqiang Index. The index helps domestic and international investors estimate China’s economic health from empirical data such as freight train traffic and electricity consumption rather than reported numbers. Following that precedent, a recent article by the American Enterprise Institute dismissed official reports and estimated the impact of Covid-19 from the frequency and occupancy of civil aviation—a special treatment reserved for China.

Modern information technology provided Beijing with a powerful remedy for the weakness of its data pool, and authorities grabbed the opportunity. The last decade saw the world’s possibly largest and most successful public-private partnership develop between government on all levels and private technology firms like Tencent and Alibaba. As great partnerships do, the collaboration blurred the borders between the two sides. Citizens of today’s China hail taxies operated by state-owned firms via Tencent’s Didi app, transfer their cash from state-owned banks through Alibaba’s Alipay and Tencent’s WeChat Wallet and contact hospitals, schools and tax bureaus through WeChat. The budding social credit system relies heavily on the same firms. When the Coronavirus hit China, the secret ingredient to the quick, coordinated and cordial introduction of movement restrictions was the hard work of data specialists in Hangzhou and Shenzhen.

But the alliance also creates new risks. Data security and privacy concerns abound, but their extent and relevance are debated in the People’s Republic. Less easily dismissed are the system’s inefficiencies. The centrality of tech firms makes data collection entirely dependent on mobile phones. But as international airlines and other mobile-dependent industries testify, problems occur as people lose, break and steal phones, power down to hide or by accident, become incapacitated or never buy one. Moreover, state authorities eventually rely so heavily on the private sector that they lack their own data resources. Aware of the risk, Beijing uses carrots and sticks to attach technology firms to the state. Tencent, Alibaba and their peers are closely scrutinised and probably controlled, but also receive stakes in multibillion public projects like the social credit system or the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). “Follow our Party, start your business”, reads the inscription of an outdoor sculpture in front of Tencent’s Shenzhen headquarters.

The balance may change eventually. The People’s Bank of China plans cryptocurrency systems to partially replace commercial apps. Until then, China’s statistical ecosystem is divided. Data on an emerging middle class is widely available, although probably insufficiently analysed. A majority underneath is more latent. China has as many mobile phones as people and about 50 percent internet penetration, which suggests blind spots with millions of people. To be fair, it’s the top that counts. China’s Gini coefficient indicates that one-fifth of the population owns most wealth and pays most taxes. Its political system ensures that most decisions also come from the same elite. But crises like Covid-19 put a pressure on a system where hundreds of millions have weak access to state services and little economic or political incentive to submit their data. Alternatives to commercial apps are rudimentary: people who struggle with QR code registrations hand-fill printed forms that may or may not reach authorities. In a population of close to 1.5 billion, those tallies add up.

In other words, Beijing’s coronavirus-related revisions are more likely to be errors than cover-ups. China has a proven record of silencing critical opinions, but its control over people does not guarantee control over data. Unfortunately, such oversight deepens mistrust between China and the world. International media, used to a system where the market generates data and the state follows, struggles with the topsy-turvy paradigm in China. They suspect treachery and conspiracy. Lack of insight into China’s workings helps those claims go viral. China suffers multiple insults. The pandemic has pushed state authorities into a global limelight, a place they despise. The pressure for transparency is enormous and, as Beijing sees it, China has done well. The World Health Organisation recognised its improving transparency. Ministers ventured lightyears from their comfort zones at televised press conferences with foreign journalists. The subsequent public poking at the nation’s hidden weaknesses probably came as a shock to the political leadership and triggered defensive reactions.

We are experiencing an unprecedented crisis that puts everyone on edge. Information is scarce, stakes are high, time is precious and nerves are raw. People under pressure create unnecessary concern, conflict and confrontation. That cannot be avoided, but the right attitude can minimise its occurrence and mitigate its consequences. Faced with China’s intimidating size, looming might and unnerving ambiguity, decision-makers must first anticipate their own inevitably emotional reactions. Yes, it will probably scare them. Yes, they may see some of their worst fears in print or on screen. That is alright. As a Chinese-Australian businessman recently told me, “Nobody trusts China—even China doesn’t trust China”. But business claims to thrive on risk and courage, which is probably why China is taking centre stage. Therefore, executives must take a deep breath and separate emotion from perception. Once they reached that clarity, they can use the former for motivation and the latter for direction.

Picture credits: Johns Hopkins University’s Coronavirus Resource Center

Be First to Comment