There has been a lot of media coverage around the recent escalation of high-level negotiations underway between China and Vietnam. Several agreements and MOU’s have been signed, with fifteen such documents having been concluded since June 2022. Vietnam has successfully promoted itself as the Switzerland of ASEAN, particularly its claims to diplomatic neutrality as it builds its export market.

This strategy has been relatively successful and attracted a number of foreign investors that see Vietnam as an alternative manufacturing hub to China. Not only has Vietnam offered attracted incentives to foreign investors in the form of tax breaks to attract low end manufacturing, such as garment making, but it is now attaching significant investment incentives for investment in the high-end tech. These incentives include reduced corporate tax, sales tax, and land tax exemptions. There is a clear focus on the microchip manufacturing market – which is no coincidence with regards to China’s sudden elevated interest in engaging with Vietnam.

Vietnam has also marketed itself as one of the most open economies in the world, clearly differentiating itself from China. It has 15 Free Trade Agreements in place and offers a fairly stable government with a roadmap to socio-economic development. Another market advantage is that over 40% of its college graduates major in science and engineering – creating a sustainable talent pool for high end technology manufacture.

A relationship of convenience

When one considers that Vietnam and China share a troubled history shrouded in heightened distrust, it would seem that the two would not be capable of building a solid economic partnership. Rather than go into the full history of Sino/ Vietnamese relations, one need look no further than the ongoing dispute over the Paracel Islands. Not only did China simply annex the Paracel’s, but it has also not honored the agreement reached in October 2011 that sought to contain the dispute over the South China Sea and the Paracel Islands.

What is material to note is that this agreement was struck with Hu Jintao when China had a more internationally engaged persona and was still developing its open China policy started by Deng Xiaoping. Arguably, it was inevitable that this agreement would come under increasing pressure as Xi Jinping introduced “Wolf Warrior” diplomacy and sidelined the more “China Open” approach espoused by the Youth League and Shanghai factions. Readers may recall the recent public humiliation suffered by Hu Jintao at the recent 20th CPC Party Congress.

The impact of this changed trajectory is highlighted by two recent remonstrations by Vietnam over the contested Paracel Islands. Firstly, Vietnam issued threats in 2019 to initiate legal proceedings through the International Court, essentially following the steps taken by the Philippine’s in 2016. The second is more recent, with Vietnam protesting People’s Liberation Army drills near the Paracel Islands in July of this year. What is material to the discussion around the relationship are the claims by Vietnam that China was violating its sovereignty.

Given that context and the opportunity created by China’s increasing international isolation, Vietnam set itself as being an attractive alternative manufacturing investment for those wanting to diversify their supply chains away from China. The success of the marketing plan would see Vietnam’s export sector rapidly grow to US$ 340 billion. China may have initially not been too concerned by the manufacturing growth within Vietnam, and essentially could be seen as fitting comfortably with the China +1 strategy. After all, Vietnam was reliant on China supply chains and could not realistically challenge China’s manufacturing prowess. Arguably the trading arrangements suited China as Vietnam’s debt to China is at a manageable level of 3% of GDP (US$ 16.3 billion). This is unlike other countries participating in the ambitious Belt Road Initiative (BRI).

A changed landscape

Early indicators began emerging in July 2022 at the 14th meeting of the China-Vietnam Committee for Bilateral Cooperation. The meeting was held in Nanning, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous region. Hosted by China ‘s foreign minister, Wang Yi, it was attended by Vietnams Standing Deputy Prime Minister, Pham Binah Minh. There were senior level exchanges that sought to consolidate strategic mutual trust, promote cooperation in various fields, advancing their respective major political agendas, and further demonstrate the strategic significance and rich connotations of bilateral relations. The parties committed to seeking greater synergy between development strategies, advance cooperation in connectivity, the Belt and Road Initiative, and the “Two Corridors and One Economic Circle” strategy (a unique application of the BRI to Vietnam).

Overall, the talks were presented as the two parties seeking to strengthen dialogue and cooperation in agriculture, pandemic response and emerging industries. However, these discussions were already pointing to supply chain issues that were emerging – particularly the use of coercion by China to disrupt Vietnam’s supply chains. Essentially, a focal point was the establishment of a mechanism for jointly ensuring stability of supply chains, with a focus on port construction and the facilitation of customs clearance.

What China was beginning to see within the Vietnamese manufacturing ecosystem, was a move of high end / technology capability. Both TSMC and Intel have moved significant microchips manufacturing and design into Vietnam. Micro-processor and micro chip design, innovation and manufacture are a key strategic weakness in Xi Jinping’s global ambitions. A key weakness that the US and the EU are exploiting through targeted sanctions and denial of access to key technologies.

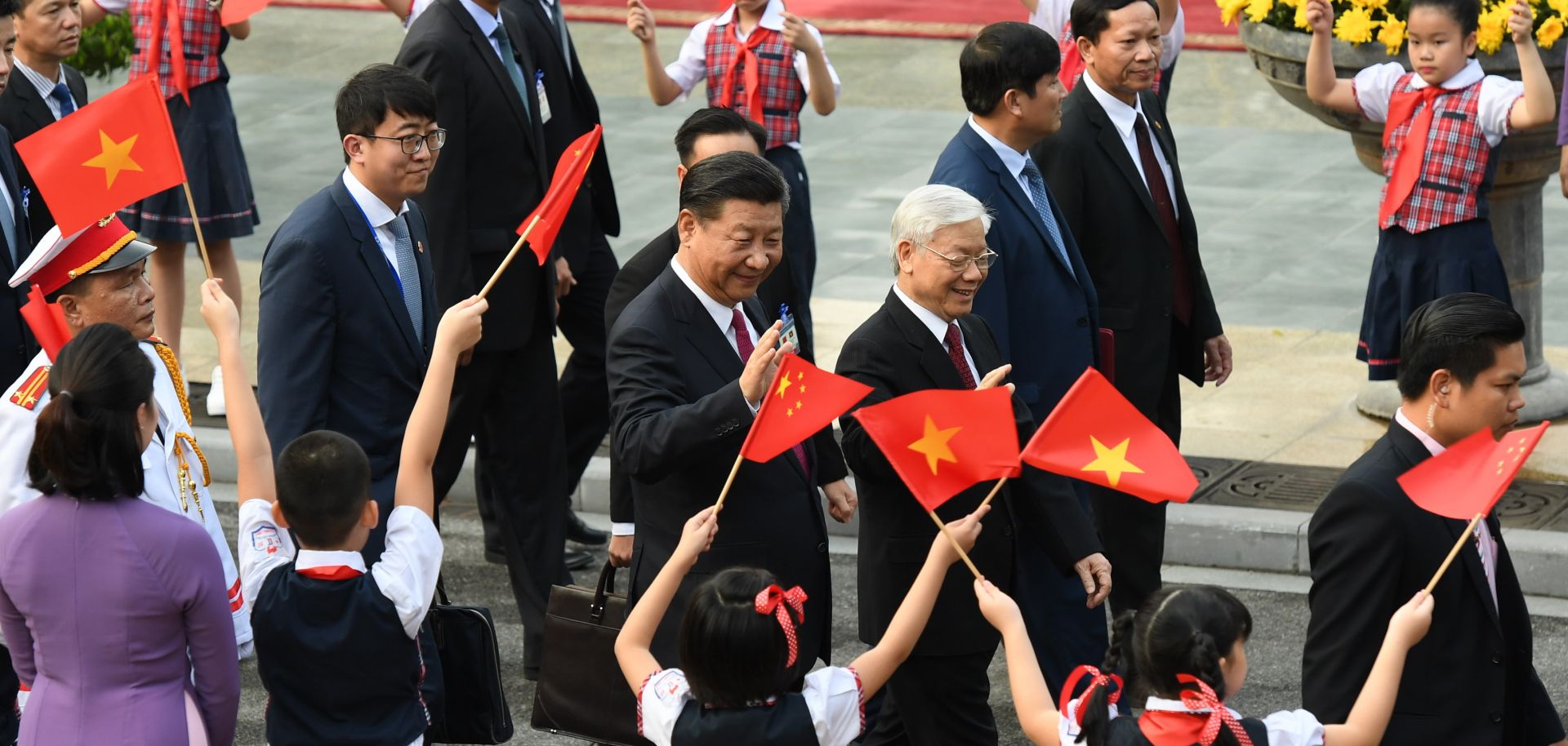

In a meeting between Xi Jinping and Nguyen Phi Trong, the respective Communist Party General Secretaries, in the first week of November 2022, there was a further undertaking to implement an MOU to enhance co-operation to ensure supply chains and to promote safe, stable production and supply chains between the two. Post meeting, they jointly announced the signing of an agreement on economic and technological cooperation, as well as cooperation documents covering agriculture, marine environments and maritime cooperation. As with many of the MOU’s signed by China, one needs to look at the intent sitting behind the agreement. Real intent is often hidden, but the intent behind this agreement is clearly seen in “technology cooperation” as China tries to address its core strategic weakness.

How did China get a rival to agree?

Essentially China weaponized its supply chain to inflict economic harm on Vietnam. Vietnam does not have the supply chain network that China has and the US$ 165 billion bilateral trade between the two was severely disrupted. Vietnam normally gets Chinese raw materials – the likes of wood and leather – to feed its factories. It makes sense that Vietnam was looking to mitigate long term problems in sourcing raw materials needed for their export sector. Some would argue that China is really trying to manage the migration of manufacturing employers from China to Vietnam, particularly as a way to circumvent US tensions.

Adding fuel to the fire, is the recognition by Vietnam that it needs to maintain its access to the South China Sea. Their prosperity is ultimately linked to freedom of navigation, and they need to protect an export driven economy. Abandoning the sea makes them vulnerable to another used China tactic i.e., a blockade of Vietnamese ports and the deprivation of Vietnam’s offshore economic interests.

Unfortunately, these strategies are familiar to the likes of Australia and the EU. Note how disrupted supply chains became in November / December 2021 when ships simply disappeared in Chinese waters when the satellite tracking systems were shut off. Furthermore, dubious customs and shipping queries by Chinese officials created delays and disrupted supply chains that did untold damage to fresh produce and agricultural products exports/imports. An example is the commercial and brand damage done to the Australian seafood export market when left to essentially rot on the wharves in Chinese ports.

What is the intent of this supply chain coercion?

The real target around these issues is for China to get access to microprocessor technology and manufacture and can be seen with recent developments in this sector within Vietnam. Samsung Electronics is investing US$ 850 million in the Thai Nguyen Province. This would make Vietnam only one of four countries that produce semiconductors for the world’s largest memory chipmaker. This announcement was made in August 2022, so the recent MOU between Vietnam and China regarding technology exchange is “well timed” after a sustained period of supply chain coercion.

There are a number of indicators that China sees the recently enacted US CHIPS Act is a major setback and supports the notion that Vietnam’s emerging semiconductor industry is of strategic importance. These indicators include China’s claims that CHIPS Act will backfire and in fact inflict more damage on US companies, using the strategy used to get Bill Clinton to give the PRC permanent preferred nation status i.e., closing trade / economic access to the China market. In this case the PR campaign being launched in the US by the CPC is to argue that the US will lose 18% of their global market share or 37% of their revenue. The knock-on effect within the US would be a loss of up to 40,000 jobs. They have extended this economic narrative to the wider global community by claiming that the CHIPS Act violate the WTO rules despite China’s many and ongoing violation of WTO rules.

Despite these claims, we note that there are a number of emerging semiconductor developments within Vietnam, including amongst others: Synopsys (a leading chip design software company) shifting its investment and engineering training from China to Vietnam; Korea’s Amkor Technology signing a deal in 2021 to create a US$ 1.6 billion semiconductor manufacturing plant in Bac Ninh; Intel’s US$ 475 million investment into its testing and assembly plant.

China’s potential leverage to circumvent US and EU technology access?

Now that China has essentially got Vietnam to the table through coercive means, they can now leverage their further encroachment via the BRI. This would include upgrading critical infrastructure, supplying digital networks for seamless and integrated export / import systems, improved supplier networks and the supply of skills that may be in short supply. This may well prove to be very attractive to Vietnam as many of these would require finance that may not suit current Western investment business models.

Vietnam’s opportunity?

In the current geo-political climate, Vietnam is now walking a delicate tightrope as it will become increasingly difficult to maintain its current preference for diplomatic neutrality. It can best protect its interests by ensuring that there are strict and enforceable intellectual property rights. By doing this it can leverage international investors across their entire semiconductor ecosystem. The downside is that it allows China to penetrate this ecosystem such that the US and EU turn their back on Vietnam for national security concerns. Failure would effectively stop access to the innovation and technology needed to be active participants in this US$ 1.4 trillion market.

Picture credits: Hoang Dinh Nam / AFP via Getty Images

Be First to Comment