Late last week, LinkedIn, a business-focused social media platform run by tech giant Microsoft, ceased its China service with dramatic consequences for millions of job seekers, entrepreneurs and managers. They, however, constitute a minority. Most users of both Chinese and international social media apps, including LinkedIn outside of China, will carry on with business as usual. The reason is simple: the departure of the last foreign social media application from China is a quiet finale to a long process of digital separation from the world, which shocks no one with a finger on Beijing’s pulse. It is, however, a good time to look back and forward for those with business interests in China.

China was a late digital adopter. It takes effort to imagine that in 1987, a decade into Microsoft’s history, Huawei was founded to develop China’s landline telephony system. “Chinese businesses had no websites, so we became their websites”, Jack Ma boasted in 2009. He would know: before he started Alibaba in 1999, his original idea was to create China’s Yellow Pages. True to the motto of its World Trade Organisation (WTO) accession in 2001, China “welcomed the world with open arms”, at least for a while. The 2008 Beijing Olympic Games and 2010 Shanghai World Expo drew global attention to China, but fame invariably brings some infamy. Platforms like Facebook and Twitter informed millions (a drop in China’s digital ocean) of news missing from local media, from environmental data to protests surrounding Beijing’s Olympic flame and visiting politicians. When the United States Embassy in Beijing started sharing readings from its rooftop air quality monitor in 2008, Chinese state media declared the initiative “not only confusing but also insulting”.

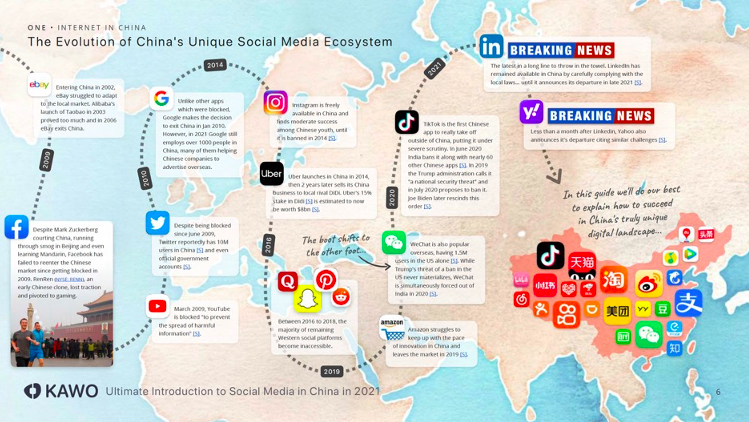

In response, from 2008 onwards Beijing systematically restricted virtual challengers to its official narrative. Facebook, Google services, Twitter, YouTube and Instagram, along with numerous social, news, data and entertainment sites became unavailable between 2008 and 2014. (See infographic.) An ad-hoc measure with weak legality first, authorities gradually developed the regulatory framework to monitor, manage and sanction a new, walled-around digital ecosystem. The State Internet Information Office (SIIO) was created in 2011, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), headed by incoming President Xi Jinping, in 2014. For institutions supporting the country’s quest for GDP growth, they developed state-run circumvention technology to access the World Wide Web. Fees run into monthly tens of thousands of dollars, ensuring separation between strategically important operations (multinational and state-owned firms, think-tanks, state organs) and more negligible ones (small and medium enterprises, cultural institutions and the wider public).

Source: The Ultimate Guide to China Social Media Marketing in 2022, KAWO, 2021

It seemed that some kind of equilibrium had been reached. Global tech firms tried to keep their remaining Chinese users by complying with hardening regulations: Yahoo, Google and LinkedIn all launched local versions with in-country servers and self-censored content. Many services including Facebook and Twitter disappeared, but few in China cared. Less than half of the population was online at the time, and only a fraction of them ever used the proliferating VPN services to outsmart restrictions. Booming indigenous apps like Tencent’s WeChat, and contenders unknown and incomprehensible to the outside world (Xiaonei, Weibo, Douyin, Youku, Xiaohongshu, Douyu, Kuaishou) comfortably covered the local market, impeding the localisation of the foreign apps still accessible. Ironically, the challenge to this well-managed success story eventually came not from abroad but from behind the Great Firewall.

Chinese innovation attracted overseas tech fans from the beginning. While incumbent tech-leaders like the USA and Japan replaced DVDs, credit cards and Myspace pages with specialist finance, social media and collaboration applications, Tencent and Alibaba developed state-sanctioned Swiss Army Knives that combined everything into easily controllable operating systems. Global tech influencers praised the convenience of this model, and inspired the concept later rebranded as “The Digital Belt and Road”: government funding for the globalisation of China’s most successful technological solutions. Execution, however, was troubled by the simple fact that any data channel opened across China’s digital Great Wall instantly became a dangerous strategic breach in Beijing’s eyes. Attempts to export debit card system UnionPay, or payment apps Alipay and WeChat Pay granted Chinese users a back door to restricted global currencies. Overseas WeChat users violated domestic content protocols; banning them undermined the app’s global ambitions.

While Chinese and global techies high-fived, Beijing faced another insurmountable dilemma. State-owned tech giants like China Mobile and China Telecom first fell behind private innovators like Tencent and Alibaba, then had to rely on them for delivering their own services. WeChat replaced phone calls and text messages. State-run telecom and utility firms collected fees and provided customer service through third-party apps. Private developers amassed influence both at home and abroad, partially due to generous Digital Belt and Road funding. A widening innovation gap threatened strategic state-run projects such as the ‘digital yuan’, a virtual fiat currency issued by China’s Central Bank. Adding insult to injury, China’s tech icons audaciously lectured Beijing. “I think that Trump serves as a reminder to the Chinese government”, Huawei founder Ren Zhengfei told Time Magazine in 2019. “That is, we should better ourselves. If not, we will be defeated.”

In subsequent years, the world witnessed frequent state efforts to curb the runaway success of the nation’s mavericks. Monopoly, data security and financial compliance regulations were tightened. Unruly superstars with record-breaking valuations were scrutinised, eliminating thinly veiled data monetising operations by firms like Ofo and Luckin Coffee. Patriotic corporate heroes became outcasts overnight. “Kill a chicken to scare the monkeys”, a Chinese proverb recommends, and national champions like Tencent’s Didi ride-hailing service and Alibaba’s Taobao store hurriedly fell in line, often self-regulating based on yet-unclear legal, financial and ideological requirements. Toutiao CEO Zhang Yiming’s 2018 public apology that the platform’s content “was incommensurate with socialist core values and did not properly implement public opinion guidance” was followed by many others. LinkedIn’s recent withdrawal from the Chinese market can only be understood in the context of those events.

Mirroring the increasing regulatory and political pressure inside China, tech firms operating in or towards its market increasingly find themselves on the spot, having to make painful in-or-out choices. Beyond national champions like Huawei and Tencent, dual pressure from Beijing and foreign governments started squeezing Chinese firms with genuine market-based business models abroad: drone maker DJI, video sharing app TikTok and many others. Conferencing platform Zoom, whose founder is a China-born naturalised US citizen, was forced last year to abandon its elaborate network connecting PRC and global servers and take sides between the Chinese and global ecosystems. (It chose the latter.) Chinese user access to all international conferencing apps has been tightened, including Zoom and Microsoft’s Teams—which brings us to the reasons why LinkedIn quoted “a significantly more challenging operating environment” while dismantling its China service.

Predictably, dramatic ‘decoupling’ narratives flourish on both sides of the Great Firewall. Sceptics lament Microsoft’s humiliation after it had diligently followed Beijing’s erratic demands, but selfishly rejoice China’s government clampdowns, interference and self-imposed isolation. “From an American perspective, there’s a bit of a sigh of a relief because China had built a better mousetrap in many respects”, gleamed the Brookings Institution in a recent article. China fans claim that foreign solutions simply could not keep up with China’s market and will not be missed. As they see it, resistance to Chinese apps, mostly by ‘the West’ but also Russia, India, Pakistan and elsewhere, come from sheer envy and spite. Neither side is satisfied, but disappointment does not necessitate disengagement. Past and present political regimes have repeatedly managed to balance internal isolation with global commerce—if in doubt, ask Saudi Arabia. China itself was a thriving commercial empire under isolationist Qing Emperors like Qian Long. Most walls have gates.

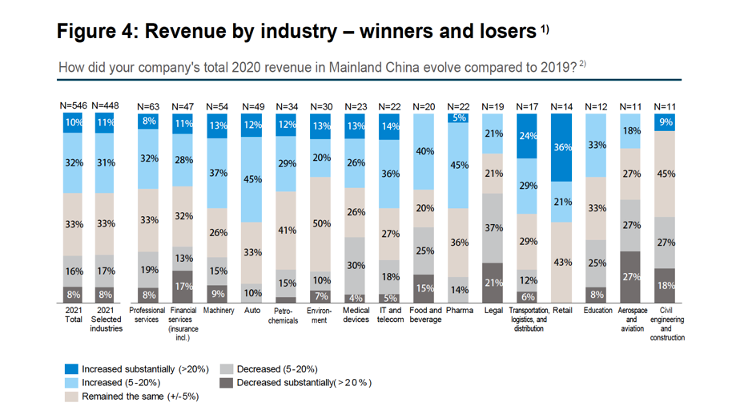

China-facing businesspeople in fright of imminent decoupling must first consider, in former WTO Director-General Pascal Lamy’s words, the “ten years of convergence followed by ten years of divergence” that took place since 2000. The nearly 15 years of “divergence” did not sever China from the world, although the rules of engagement have changed. Beijing has spent that time strategically wedging the state between local users and international service providers, a tendency likely to continue. Consequently, some business models involving digital outreach to China are more sustainable than others. Most at risk are services providing direct content to individuals through foreign technology, such as lessons, games, films, literature, research, financial and social apps for business networking, dating and friendship. More viable services engage China through interlocutors owned or controlled by the state such as consulting, legal and investment services, as well as gateways for those interlocutors towards the outside world.

Source: Business Confidence Survey 2021, European Union Chamber of Commerce in China & Roland Berger, 2021

Successful foreign-Chinese partnerships often avoid attention. Google browsers, Docs, Books and branches like YouTube are banned from China, meanwhile the company helps large Chinese firms (including state-owned ones) to reach global audiences from its high-rise offices in Shanghai. Consultancies like Roland Berger, McKinsey and EY assist the same clients with anything from listings on foreign stock exchanges to promotional strategies on sites banned in China itself—state-run news agency Xinhua has over 40 million Facebook followers. Recently revealed ‘Pandora Papers’ show Chinese state-owned firms as the most diligent founders of offshore firms in the British Virgin Islands and elsewhere. Foreign wealth managers and insurance brokers help well-heeled Chinese patrons invest in officially off-limits assets via virtual brokers and crypto currencies. Surrounding them is a thriving community of small firms, local-foreign joint ventures, startups and freelancers diligently crafting WeChat posts, TMall stores, Xiaohongshu campaigns and other Mandarin-language services for hand-crafted Estonian cider, Camper boots, Ferraris and everything else.

Few people deny the mounting barriers that Beijing erects in the way of the free movement of people, goods, money and information—where opinions differ is the rationale and eventual outcome of those restrictions. What is often overlooked is how commerce, including commercial technology, thrives on risk and the way it finds the way over, around or through the cracks of obstacles. Did someone predict the success in the Chinese market of iPhone, a mobile device whose selling propositions were double price and maximum privacy? Or Tesla, an electric car maker invited by the Chinese government to outcompete local firms? If they did, nobody took them seriously. We have equally little idea about the next global tech champions to bridge or breach the Great Firewall, or invent virtual interaction tools equally palatable for local users and for Beijing’s regulators. Whoever and on whichever side of the wall they are right now, ‘decoupling’ is not the word scribbled on top of their office whiteboard.

Picture credits: innovation-village.com

Be First to Comment