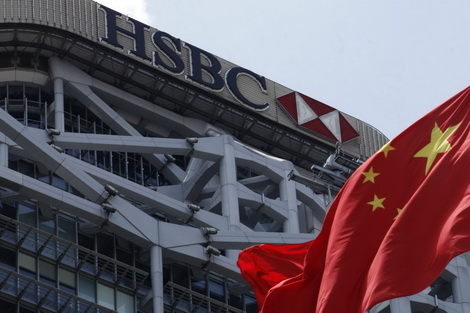

On June 9, 2020, the US Department of State issued a press statement on “China’s attempted coercion of the United Kingdom”. In the statement, Washington reiterated its commitment to stand with its allies and partners against the Communist Party of China (CPC), which the US accuses of having “threatened to punish British bank HSBC and to break commitments to build nuclear power plants in the United Kingdom unless London allows Huawei to build its 5G network”.

The support which the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corp. (HSBC) demonstrated in relation to the new Chinese security law in Hong Kong, through a petition signed by Asia-Pacific CEO Peter Wong, led to the harsh criticism by the United States. In particular, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo criticized China, going as far as linking the bank’s supportive action in Hong Kong to the words of Chairman Mark Tucker, who warned London against a ban on Huawei’s involvement in the deployment of 5G technology in the UK. The United Kingdom initially opted for allowing the Chinese telecommunications giant to take part in the development of its periphery 5G network last January, but delays caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and increased Washington pressure to bar Huawei from participating seem to have all but annihilated its chances.

Nonetheless, the future of the British bank and that of the Chinese ITC giant could be intertwined by several overlapping factors. According to China’s Global Times, there may be evidence of a “trap” set by HSBC against Meng Wanzhou, Huawei’s Chief Financial Officer and daughter of Huawei’s founder and CEO Ren Zhengfei, who has been under detention in Canada since 2018 at the request of US authorities on charges of defrauding financial institutions in breach of US sanctions against Iran. Central to the US legal case against Mrs Meng is a presentation that she allegedly gave to HSBC in August of 2013. If these claims are proven to be true, the Shanghai-based newspaper wrote, the reason behind HSBC’s participation in this move against Huawei could be seen as an attempt to patch things up with the US Department of Justice following the numerous money-laundering scandals that tainted the bank’s reputation in the US. In spite of HSBC’s claims that it collaborated with US authorities only as required by law, China has expressed its reservations about welcoming in the future foreign banks which “harm the development of China’s high technology”.

Recent news demonstrate, once again, how easily the US-China technological rivalry can extend across countries, sectors and businesses. Since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, relations between Beijing and Washington have deteriorated further. In this context, the technological competition has reached new heights and now unfolds on any and every occasion, giving rise to an endless succession of tit-for-tat moves and counter moves from each side. A recent illustration is the US Department of Commerce adding on May 22nd 33 Chinese companies and institutions to its list of entities considered to have ties with the government in Beijing and to pose a threat to US national security. It is interesting to note how, as of June 5, in the 320-page Supplement No.4 to Part 744 – Entity List published by the US Bureau of Industry and Security, 74 pages are dedicated to entities from the People’s Republic of China.

As argued by this author in a recent report published by Wikistrat, the post-pandemic world will exacerbate techno-nationalism, also meaning that a greater number of global payers – states, companies, banks or various types of organizations – could be exposed to additional stress and get caught in the middle of the US-China tug-of-war in many different ways. They do not operate in a vacuum, and political diatribes can easily affect them. Washington will continue to push against Beijing by implementing defensive strategies mainly characterized by a campaign to pressure its own allies to put an end to cooperating with Chinese tech companies. Beijing, on the other hand, could probably use a more assertive tone and expand its techno-influence along the Belt and Road, embracing partnerships with new nations and organizations.

For global companies, developing a “defense shield” is no easy task but the first step consists in understanding that not only Chinese tech companies are subjected to the pressure generated by the ever-deeper chasm between China and the US. If decoupling between the two countries (and potentially, their spheres of influence) is to go any further, a world split into two opposing forces will result into any course of action pursued by external actors to call for a reaction from the opposite side. This scenario creates a much more tense environment, where operations, public-private alliances, as well as issues such as reputation and corporate responsibility will be restructured along a new fault line.

Picture credits: China Daily

Be First to Comment