Xi Jinping, the enigma, or as I suggest in this analysis, Emperor of China’s destiny, is the reason for this paper. To explain why I see him as the Emperor, or “Son of Heaven”, exceeds my original intent of discussing the meaning of Chinese narratives during the trade war and pandemic. The reason that Xi and China are enigmatic is simply that the West doesn’t understand the East. The point of this paper is to show primarily Western thinkers that Xi, like ancient Emperors, Mao and others, sees the world through a very different lens than the West. The lens is his own unique, Eastern narrative and, without narrative analysis, he, China and their intentions will remain largely mysterious to us in the West. In order to shed light on the mystery of Xi and his designs on China’s destiny, we must remember that Xi’s perspective and current actions are but the latest few hundred meters in a journey of thousands of kilometers, at least 4000 years old.

To understand Xi’s intent requires narrative analysis so bear with me for a couple of short paragraphs about narrative. Narratives, though commonly mentioned, are poorly understood in modern discourse. As that narrative is about meaning through the lens of identity, this paper represents the meaning revealed by analyzing 4,000 years of Chinese identity. Narrative analysis always reveals identity trends that will be of interest to strategists.

The next paragraphs are an essential guide to understanding Xi’s perspective.

Narrative

If you don’t remember anything else about narrative, remember that it is primarily about meaning and identity. In fact, narrative is how humans process all that occurs around them and convert the experiences into a sort of story that gives it meaning. The conversion process delivers a uniquely different meaning for everyone based on their own unique identity. Everyone’s specific narrative identity is made up of countless layers. Sometimes, there is little difference between how two people are experiencing things and sometimes not. This depends on how many layers you share with others experiencing similar things.

All of us share layers with family, extended family, friends, ethnicity, traumas, national, collective or individual etc. Because layers are shared, there are common identity traits that define nations, ethnicities, regions etc. The more shared layers, the tighter the bond and more pronounced the traits. A large number of tightly shared traits often end up creating trends within the groups that share them. If you well understand narrative, those trends are somewhat predictive. These are the type of generic predictions that strategists look for in competitors and adversaries.

Narratives have narrators and for this article, I am the primary narrator. As the narrator, I’m interpreting Chinese history as a western writer, who is narrating a story in English about modern Chinese ascension, based on their historical identity. The reason for narrative analysis is simple. In order to strategize for war, competition, business or otherwise, you must fully understand your adversary. Without narrative identity analysis, the understanding will always be significantly incomplete.

Let’s talk about China (or 4,000 years in a few paragraphs…)

The US national security community, especially the Department of Defense, is very fond of quoting an ancient Chinese fellow by the name of Sun Tzu, an Eastern Zhou, Spring and Autumn period scholar, general, philosopher and author. He is generally credited with writing the book “The Art of War”, replete with strategy and philosophical concepts about war, among other things. While the entire book is a profitable read for business as well as warriors, it is also offers multiple insights into China’s strategy of ascension… if you understand narrative.

The parallels of Sun Tzu’s lessons and Xi’s actions are eye-opening for those in the West, if they are not already familiar with them. “The supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting” is possibly the most famous of quotes from the book and the quote most appropriate to understanding his intentions for China to achieve their goals of regional hegemony by 2035 and global by 2049.

The following three quotes are also of keen relevance to this paper. By tradition, China doesn’t see the distinction between war and business as we do in the West. In fact, Xi doesn’t see the world as we do. From his perch atop of Chinese hierarchy, China is the middle of the world, or the Middle Kingdom.

- “There is no instance of a nation benefitting from prolonged warfare.”

- “Victorious warriors win first and then go to war, while defeated warriors go to war first and then seek to win.”

- “The greatest victory is that which requires no battle”

So many of Sun Tzu’s quotes are studied independently in the West and, like all stand-alone thoughts, don’t convey the same meaning as when taken in context. With narrative as my specialty, I see The Art of War as Sun Tzu’s insights into traditional Chinese identity and how it impacts, manages and organizes competition, warfare and combat. I see each quote as one stitch in a richly woven fabric of the modern Chinese approach to pursuing their destiny, achieved via methodology as foreign to the West as it is intimate and intrinsic to Chinese identity. In other words, we in the West, so aligned, are clueless as to what Xi knows both consciously and unconscientiously.

Much like Japan prior to WWII, China’s modern military may look much like Western peers but that is more a product of technology and military hardware than concept. Strategy though is a mixture of modernity and part historical Chinese identity. This applies to the commercial arena as well. Just because Chinese companies use Powerpoint and videoconferencing doesn’t mean their long-term strategy mirrors Western equivalents. In fact, the private sector isn’t necessarily private in China and Xi sees it as a tool of state. A recent headline in the Asia Times on 16 October 2020, very bluntly makes this precise point: “China deploys Sun Tzu to win the chip war”.

The hegemonic aspirations of Xi, as interpreted by the West, is a concept based on Greek and Roman philosophy. What Xi sees, based on his narrative identity, are some of those trends discovered through narrative analysis. The shortest, over-simplified version of Xi’s endgame would be a global tributary system described as something like the following:

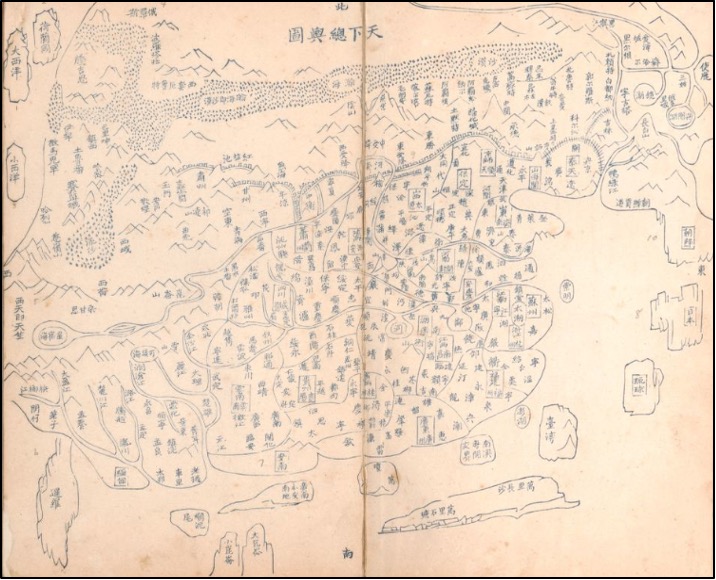

The world, All-Under-Heaven, is one, with China / the “Middle Kingdom” at the center and at the pinnacle, is an Emperor or “Son of Heaven”, the sole interface with heaven with no peer. The Han are the “enlightened”while everyone outside is “barbarian” and seeking a tributary relationship with enlightened China for commerce and protection. Those who do not voluntarily seek tributary status must be persuaded or conquered militarily. This will unify All-Under-Heaven under the Chinese paradigm of world order.

Now that we see the short form of the Chinese narrative of acquisition of what they see as their rightful place under heaven, our original point regarding “China’s narrative in relation to its US-based businesses in the midst of the current trade and technological war” comes into focus.

The only question remaining for the West, or in China’s perception “those of us in barbarian lands”, is: do we wish to be tributaries of Beijing or not?

Breaking down strategy

Like any business or military strategy, knowing where the competition/adversary is heading and how they will get there is critical to developing your own strategy. “The China dream”, or “to realize the dream of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” is Xi’s intent to acquire, in Western terms, global hegemon status by 2049. The ultimate form of hegemonic status would be the tributary system as described above.

Laid out by Xi in a now famous 2012 speech, achievement of global hegemony by 2049, in time for the Centenary of the CCP, is the ultimate goal, even though there is debate regarding the exact meaning of the language used. Many Western strategists and analysts also see 2035 as the target for regional hegemony and a milestone en-route to 2049 global hegemonic status. Again, I use the word “hegemony”, a Western term for ease of understanding.

Unlike the West, Xi, in a role closer to Emperor or “Son of Heaven” status, has control over all aspects of his strategy. This stands in stark contrast to each nation and each individual company or corporation outside of China. States not already in China’s orbit or semi-tributary status are mostly on their own, save an occasional treaty, alliance or semi-formal grouping of interests such as the QUAD or ASEAN.

Xi’s approach is what we in the West would consider as “soft power” because he isn’t merely running the nation, he is embarked on an extended campaign of empire, using all of the tools at his exclusive control and, as with Sun Tzu, “avoiding open conflict at any cost”. With the US recently abdicating its global leadership role, capable of offering a counter-balance, Xi can simply keep applying pressure to individual nations, corporations and small alliances until they, per the narrative, “seek tributary status”.

In the past few years of research and looking deeply into the dusty corners of anthropology and history for strategy trends, I am again finding the trend lines I had hoped for regarding Xi’s intentions for China. China is no different from other nations or peoples with a long history. The trends of power acquisition and sustenance leap from the pages under the scrutiny of narrative analysis. Combined, the identity traits or trends in this case, are the highway Xi is traveling towards “rejuvenation” and, Tianxia, “all under Heaven”.

Xi navigates these highways in a manner uniquely suited to the modern world but make no mistake, his maneuvering would be as recognizable to ancient, dynastic elites as they would be to modern Chinese leaders. In many ways, the CCP is just a modern form of 2nd century B.C.E. legalism shaped by Mao as the administrative structure of the PRC. Because we know the meaning of how Chinese historical figures, based on their specific identity, accomplished empire, we now know something about where Xi, self-styled on ancient historical figures like Qin Shi Huangdi and others like Mao, is going.

What is the Chinese narrative of empire?

To understand where Xi is going, we needed to know where he is coming from. Again, without getting bogged down in the technical debates between the interpretations of respected sinologists, Xi’s endgame is as previously described.

China, across more than 4,000 years of history and through a variety of dynasties, philosophical and religious beliefs, has sustained in varying forms a handful of narratives that Xi has woven into the fabric of the China he intends to create or, more accurately, re-create. Like Mao and other emperors across the millennia, he has changed the names of concepts but they are still recognizable as identity traits of historical Chinese narratives. The main points of his historical meta-narrative include the following descriptions of supporting narratives:

- China as the “middle kingdom” at the center of “all under heaven”;

- The middle kingdom is ruled exclusively via an emperor of sorts or “Son of Heaven”;

- The emperor uses a system that could as easily be interpreted as legalism or as Maoist to administer the world;

- Those within China are enlightened and Xi’s pursuit of purging China of non-Han fits with another historical narrative;

- Those outside of China are “barbarians” seeking enlightenment via their interactions and commerce with China;

- Those who seek to establish a positive, commercial role with China become “tributary states” and benefit from China’s commercial network as well as her protection of that network;

- All who don’t seek such a relationship are to be dealt with militarily;

- All under heaven are responsible for abiding by the world order China installs as it pertains to commerce, peace/war, while free to some extent to sustain/maintain their own traditions. This of course is only appropriate so long as it does not interfere with the Emperor’s plans.

So, what is so bad about a functioning global system?

In theory, a unified Chinese world order sounds less than a severe threat, but a review of Han historical narrative also leads us to problematic identity characteristics. For our purposes, I will only highlight the three most prominent and problematic identity characteristics that we need to be concerned with. All three are historical trends, extending far past the unification by Qin Shi Huang a couple of hundred years BCE.

- Human rights abuse and disregard for all human life and property;

- Military intimidation;

- Economic leverage exercised mercilessly.

Historically, Life for all, including court elites, beneath the Son of Heaven was fraught with peril and held little value, an especially notable trait under the first Han emperor’s legalism system which both Xi and Mao have somewhat reincarnated as the CCP. A very simple explanation is that men are relatively valuable so long as they provide value to the nation, originally via the military or farming. As we can see in Xinjiang, Tibet and in modern versions of tributary or semi-tributary states like Kenya, Sri Lanka or Myanmar, the same disregard for human life prevails so long as the state benefits.

Merciless economic/commercial leverage has become the hallmark of Chinese commercial partnership in places like the Philippines, Sri Lanka, much of Africa etc. Xi’s narrative of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is grounded in the concept of being mutually beneficial while in truth, partnerships look more like borrowing money from a bookie. China may not collect on their leverage until she needs something but be assured, she will collect and the cost will be exorbitant.

Finally, military intimidation is always an implied threat, especially in areas more proximate to China proper. The South China Sea is an obvious example. The concept of the only rules that matter are Xi’s is ever present and he’s building a world class military to ensure that no one mistakes the “muscle” behind his publicly polite “requests”.

These three prominent issues are important to understand because Xi and likely his successor is intent on achieving the “rejuvenation” that puts China at the center of the world and based on her rules. The dedication to empire or Tianxia is not a “want to do” for Xi. He has framed his ambition as the rightful order for the entire world and made it China’s destiny, not his.

China, is without a doubt on a path defined by historical narratives. The primary vehicle of their ascension is the BRI, itself woven intricately into Chinese history. Any nation, alliance, corporation or business would do well to understand that you are, in Xi’s mind, filling a role in the historical narrative he’s translated into modern China’s destiny. Ultimately, all power and profit is the state’s and on China’s terms. Based on China’s behavior in the Xi era, this completely will undo the international order as we know it.

The only foreseeable answer is unity of the global world-based order that collectively can provide the counter-balance to a stronger, wealthier and more influential China. China, like most nations, can have their ultimate vision modified by circumstances. History has often demonstrated the folly of world domination for the overly ambitious.

Picture credits: map “Tianxia – All Under Heaven”, circa 1890, Library of Congress

Be First to Comment